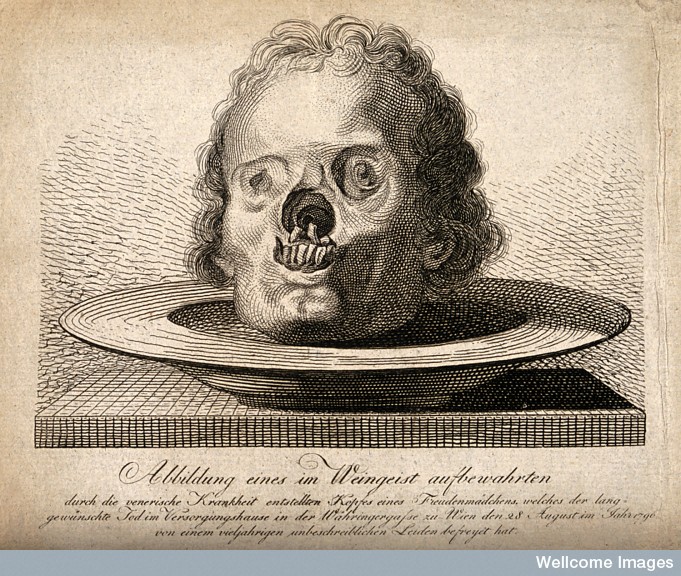

Should you visit The Hunterian Museum you can come face to face with victims of the great pox (syphilis). As you enter the main museum from the staircase, to the left hand side, on the topmost shelf of a cabinet containing a series of human specimens there is a set of skulls showing the ravages of what is now known as tertiary syphilis, the disease’s most aggressive phase.

LHS: Syphilis of the Skull, Hunterian Museum & Art Gallery collections, catalogue number GLAHM 122592. RHS: Syphilis of the Skull, Hunterian Museum & Art Gallery collections, catalogue number GLAHM 122590.

William Hunter, as is evident from the collection that he bequeathed to the University of Glasgow, was a voracious collector with incredibly diverse interests. But why did he collect these specimens?

Well, it seems these bones were principally objects of medical-scientific interest for Hunter. Perhaps he even used them in some of his teaching. In any case, neither these skulls nor the disease that they illustrate were Hunter’s primary interest. This is reflected in his catalogue of anatomical preparations. Some of the entries in this manuscript carefully document the origins (and sometimes even synopsise the life-stories) of human and animal specimens. However, no record is made of where the pox specimens were acquired from, and no clue is given to the victims’ identities.

We know very little of Hunter’s own perspective on the disease and its victims. In 1775 he gave a paper to the Royal Society in London, discussing the geographical origins of the disease. During this paper he suggested the pox was associated with ‘immorality’ and ‘disgrace’. However, it is unclear whether Hunter shared this opinion or was merely acknowledging contemporary attitudes.

But these skulls are not just ‘specimens’, they are human remains. They lived lives as vivid as our own. The holes in some of the skulls can look like the accident of a careless archaeologist. It is easy to forget when browsing in the museum, that these people watched, and likely suffered unimaginable pain, as the pox ate away their bones. These painful and emotional experiences cannot be captured by museum labels or catalogue descriptions.

One of the aims of this project, particularly through the Insight Talks I have delivered in The Hunterian, has been to ask museum visitors to consider how they view the objects and specimens on display. To acknowledge the scientific and medical importance of items like these skulls, but also to encourage viewers to consider these as emotional objects, which suggest a past that we cannot fully access. Ultimately, without documentation we cannot hope to discover the stories of these individuals, but through combining our knowledge of medical history, the attitudes towards and treatment of the pox, alongside our own emotional experiences of illness, we can give some flesh to these bones and see them not only as specimens, but as people.

A preserved skull of a woman who had been suffering from syphilis and encountered her ‘long wished for death’ on 28 August 1796. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.