‘The pestilent infection of filthy lust’ – William Clowes, A … treatise touching the cure of the disease called (morbus gallicus) (London, 1579).

‘[the great pox] has the direful Attendants of Shame, Reproach and Ridicule.’ – John Profily, An easy and exact method of curing the venereal disease (London, 1748).

From the sixteenth century until today there have been those who have strongly associated the pox, syphilis, and other sexually transmitted diseases with shame and who have stigmatised those who contract these infections.

During the eighteenth century some people argued that medical practitioners ought not to cure those who contracted the pox. It was, they contended, a disease spread through sinfulness, and therefore a just punishment for any who contracted it. They argued that the potential to readily obtain a cure encouraged those who contracted the disease to persist in their debauched lives, thus infecting British society with an epidemic of immorality.

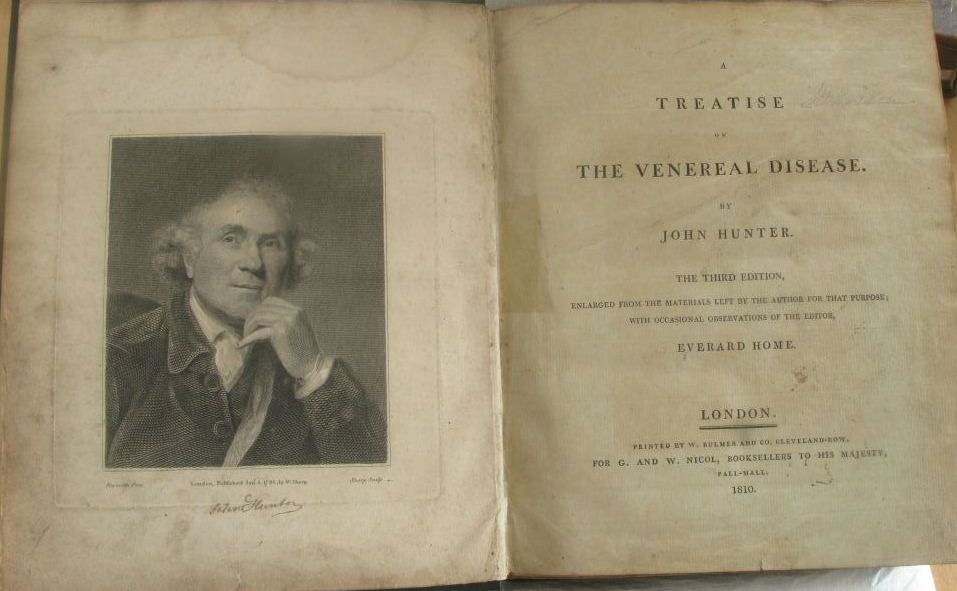

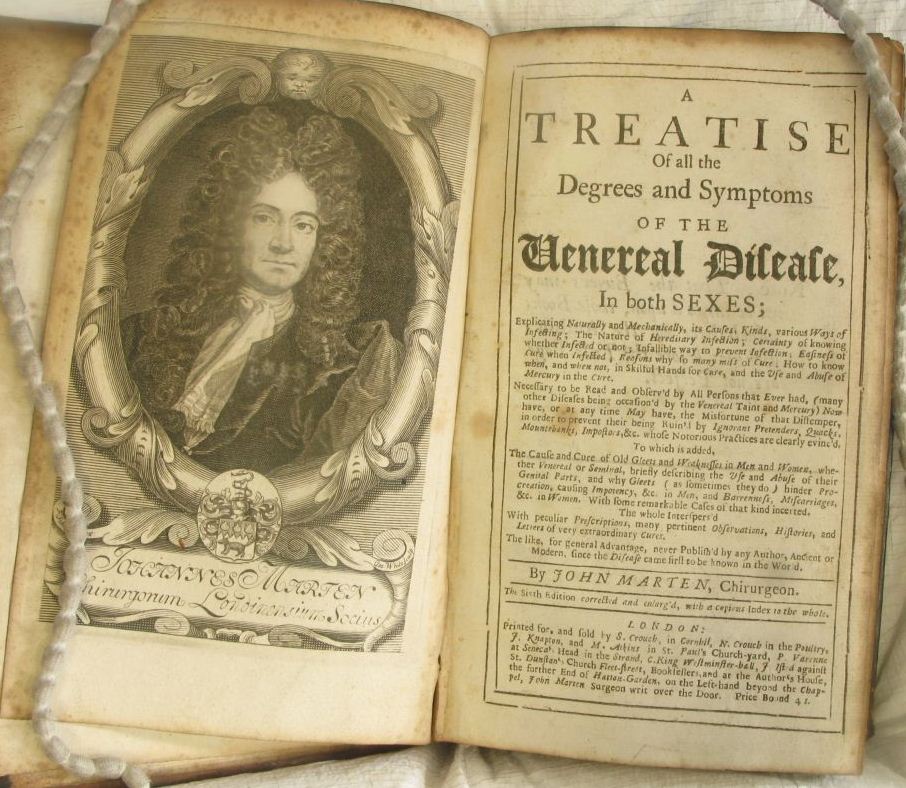

However, not everyone agreed with this line of thinking. The London-based John Marten wrote:

But I must declare, I cannot be of their Opinion, because it seems to shut out Charity, which at least however ought to be afforded to our Fellow-Creatures in Misery; And besides we are all frail, the same Flesh and Blood as others all subject to the same Venereal Pleasures. (From: John Marten, Treatise of all degrees and symptoms of the venereal disease.)

Indeed Marten’s treatise is one which treats some pox victims in a very sympathetic manner, showing us that the reaction to the pox was not uniformly negative. He emphasises that there were numerous victims of the disease who contracted it through no fault of their own – citing many cases wherein an adulterous husband (and occasionally wife) gave the disease to their faithful and unsuspecting spouse. In these cases he is always very much at pains to emphasise the innocence of the faithful party.

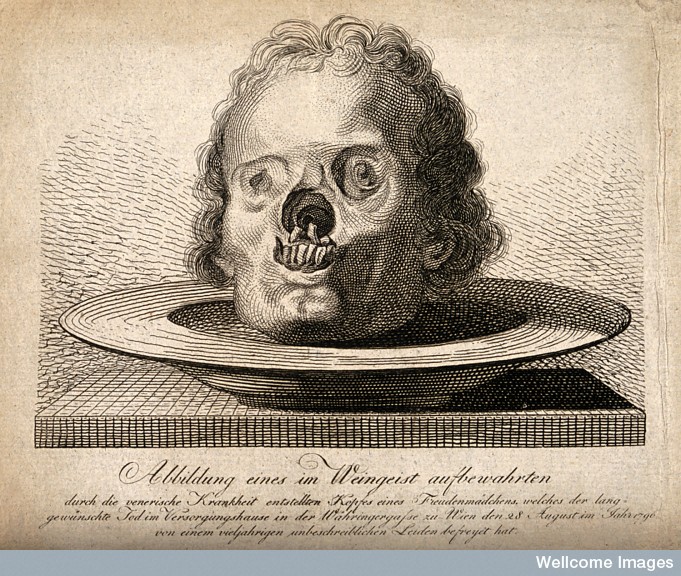

Nevertheless, single women who contracted the disease were in particular danger of stigmatisation. Eighteenth-century ideals of femininity idolised faithful wives and pure virgins. Some writers warned that women were especially deceitful and would use makeup and cosmetic strategies to trick men for financial gain, infecting them with the pox in the process.

Whilst Marten believed that a few innocent female virgins were infected through violence or seduction, he strongly condemned the many women whom he perceived as lacking sexual morals (i.e. those who had sex outside of marriage). In his Treatise he included some advice for his male readers. He urged them to find a pocket-sized portrait of a beautiful woman, and then to diligently deface it, erasing the nose, giving it rotten teeth, etc. They were to carry this image about with them and to look upon it when they had ‘a fancy for a woman’ to remind themselves of the sin and disease that apparent beauty could conceal.

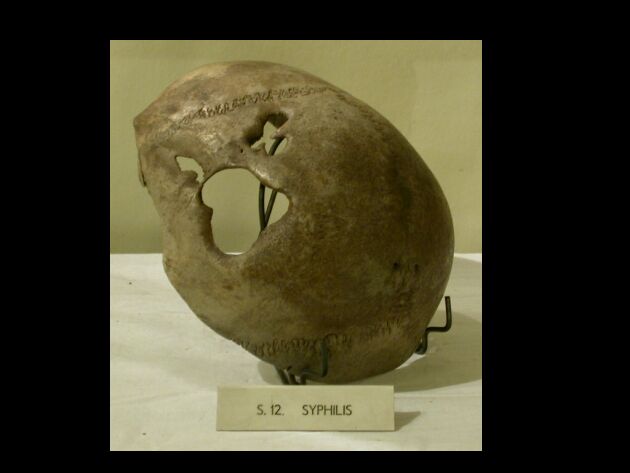

Syphilis remains very present in global society. In England the diagnosis of syphilis has increased by 76% since 2012 (rising from 3,001 diagnoses in 2012 to 5,228 in 2015) and in the US rates have also been increasing. When reading about the stigmatisation of pox victims in the eighteenth-century, it is very easy for us to shake our heads, to say ‘wasn’t that awful, well things are better now’. But are they? Whilst more effective care is more readily available in some areas of the world, have societies’ attitudes progressed toward STDs, women’s and non-hetrosexual sexualities?

‘Interviewer: And what comes into your head when I say sexually transmitted infection, or STI to you?

Participant: You shouldn’t really say it ‘cos anyone can get them but kind of, more it’s perceived as slightly, not dirty people but kind of more promiscuous, stuff like that…(i24, man, aged 16–19)’