In 1495 Europeans began to remark on the appearance of a new ‘terrifying, troublesome, and painful sickness’. Those afflicted suffered from aching bodies covered with ulcerations, and pustules which could ooze and stink. In its most horrific form the disease rotted the bones of its living victims, and one contemporary described how those afflicted wished ‘to die as soon as possible’.

Many thought that the disease had begun its spread in the wake of the siege of Naples by King Charles VIII of France. They believed the disease had spread northwards through Italy and beyond as his soldiers and mercenaries had returned home to France, Germany and Switzerland. Thus it became known as the ‘French disease’ and the ‘Sickness of Naples’, although it quickly gained other names too, including the ‘great pox’ and the ‘Plague of Job’. Today archaeologists and historians are still debating the origins of the disease. Some contend that it was brought back from the New World by Christopher Columbus’ men, but others argue that it developed from diseases already present in Europe. Whatever its origins, the disease spread with incredible speed reaching Scotland by 1497 and Russia by 1499.

The opening image from, Tractatus de pestilentiali scorra, Joseph Grünpeck (Augsburg, 1496), University of Glasgow Library, Hunterian Bx.3.38, with permission of University of Glasgow Special Collections.

The great pox struck fear into the hearts of Europeans whose doctors struggled to identify, let alone cure this new pandemic. Heated arguments about its causes emerged. Some believed that it was spreading through the air, or through sharing cutlery and clothes. Others emphasised its sexual nature, noting that the first ulcerations usually appeared on the genitals. Whilst physicians argued about its earthly causes, many believed that ultimately the disease was a punishment from God. For example, on 7 August 1495 the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I, issued his Blasphemy Edict, which claimed that sins such as lust, swearing and intoxication had angered God and caused him to send the new disease. By the eigtheenth-century, the sexual transmission of the disease was agreed by most doctors, with very few still adhering to non-venereal theories of transmission. And although doctors were more focused on its earthly causes, its associations with sin, especially immoral sexual practices, remained strong.

Even more worryingly, it was not only the causes of the pox which posed a problem. Initially many doctors believed the disease to be incurable. Various remedies were attempted, including herbal mixtures and bloodletting. However, by the mid-sixteenth century doctor’s felt the disease was curable after all. By this time two preferred treatments had also emerged: guaiacum and mercury, and the use of these remedies persisted through the eighteenth-century.

Drug jar for mercury pills, Faenza, Italy, c.1731-1770 (Library Reference No.: Science Museum A42768), Wellcome Library, London.

Guaiacum was a bark imported from the Americas, and was usually consumed as a drink or decoction, made into a sort of tea, sometimes with the addition of other medicinal herbs. However, this imported cure could be expensive or difficult to obtain. Some physicians also argued that it was ineffective. Therefore, mercury became the most common treatment for the disease. It could be administered internally, swallowed as pills, or externally, as a lotion rubbed onto the body with the patient then often being wrapped in blankets or being left by a hot stove to sweat (see image below). Today we know that mercury is highly poisonous to the human body and many early modern physicians recognised that the treatment was excruciating and harmful to the body. Yet they saw it as their best hope against the disease. One eighteenth-century surgeon, John Marten, commented that ‘a desperate Cause must have a desperate Cure’.

A patient undergoing sweating treatment: first they sit wrapped in blankets on a chair, beneath which is a flaming spirit stove (Fig.1) and then get into bed (Fig. 2) staying wrapped up. Sweating Treatment for Syphilis, engraving by J. Harrewijns, from: Venus belegert en ontset by Stephen Blankaart (1685), Wellcome Library, London.

However, these treatments were not always successful, and indeed the mercury must have poisoned some patients. Moreover, today it is recognised that syphilis (believed to be the same or highly similar to the pox suffered in the eighteenth century) can enter a dormant phase wherein it appears to have disappeared, although it can later re-emerge. The disappearance of the symptoms would likely have led some early modern medical practitioners and patients to believe that the disease was cured. A failure to recover or a relapse of the disease (usually interpreted as a new infection) were often blamed on the patient, who could be accused of failing to follow doctor’s orders or for having an immoral lifestyle that led to reinfection. These moral judgements persisted into the eighteenth-century and are something that I will be exploring in more detail in an upcoming post.

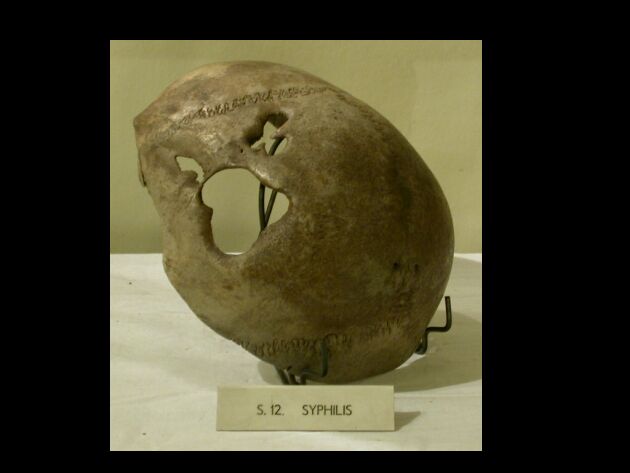

Indeed, despite being present in Britain for around 200 years, interest in the pox had not diminished by the eighteenth century. It was during this period that William Hunter collected a number of human skulls disfigured by the disease, one of which is shown in the image below. These skulls illustrate the devastating impact of the pox; the deformation and disintegration of the bones seen in the image below would have taken place during the victims lives. The pain and suffering caused by the disease which was first remarked on in 1495 was far from over. Marten recorded the extreme fear that the disease caused amongs his patients, and an upcoming post will explore how the spectre of the disease haunted their lives.

Syphilis of the Skull, Hunterian Museum & Art Gallery collections, catalogue number GLAHM 122590.

Of the 242 printed medical texts on the pox (dating from 1496-1820) in the university’s Syphilis Collection, 84 were published in Britain during the eighteenth-century. Clearly, the pox remained a central issue in medicine. However, it also provoked moral and emotional questions and responses. Marten remarked that there were those who caught the disease both ‘deservingly’, such as those who slept with prostitutes, and ‘undeservingly’, often through infected spouses. The next posts in this blog will therefore explore how these distinctions between deserving and undeserving victims arose, alongside the variations in responses from reproach to sympathy that we find embodied in the collection’s texts.

Pingback: ‘Hypochondriacal People’: Lives Haunted by the Pox | Pox and prejudice?

Pingback: Medical Fascinations, Human Lives: Hunter’s Syphilis Specimens | Pox and prejudice?